In 1923, Claude C. Hopkins, who was probably the most famous (and well paid) copywriter in American advertising wrote a short book about how he did what he did. He called it Scientific Advertising, a title he felt would separate his serious approach from what he felt was the highly idiosyncractic, arbitrary, and, most sinful of all, wasteful business it had been before he showed up. It also (and not accidentally) advertised to potential clients why they should bring their business to Lord Thomas. Sort of a portfolio, rainmaker and business book all in one.

Like Blake says, always be closing.

But first and foremost, Hopkins is a man on a mission, compelled, like many in the 1920s to use technology and numbers and science to avoid the kind of idiocy that culminated in, and was buried upon the fields of, World War I. And because he is, Hopkins doesn’t so much talk to you as shout, as from a pulpit with the spirit of a vengeful and righteous Advertising God coursing through his veins.

For Hopkins believes that there are right ways to do things and wrong ways. He believes there are specific reasons for creating advertising (“The only purpose of advertising is to make sales… It is not to keep your name before the people.” p. 220). That there are mistakes people make when thinking about creating advertising (“Ads are planned and written with some utterly wrong conception. They are written to please the seller. The interests of the buyer are forgotten. One can never sell goods profitably, in person or in print, when that attitude exists.” p. 225). That there are mistakes people make as they are making advertising (“That is one of advertising greatest faults… They forget they are salesmen and try to be performers. Instead of sales, they seek applause.” p. 223). That advertisers overestimate the public’s interest in their work (“No one reads ads for amusement, long or short” p. 222). That advertisers over-estimate the public’s interest, period. (“People are hurried. The average person worth cultivating has too much to read. They skip three-fourths of the reading matter which they pay to get.” p. 238)

And on and on and on.

And the thing is, he’s right. Follow these simple precepts and you will not go wrong. Advertising is about making sales, not applause. It’s about what the customer needs, not what you want to sell them. Because they’re busy. Because they’re self-involved. Because they just don’t give a damn about you. And that’s true in a print ad, a tvc, a facebook app, a promoted tweet or whatever has been invented since you started reading this essay.

There is one place, however, where there is a curious discrepancy between Hopkins’ time and ours. On p. 301 he writes “Sales made by conviction – by advertising – are likely to bring permanent customers. People who buy through casual recommendations do not often stick. Next time someone else gives other advice.”

Today it’s exactly the opposite, of course. Today, advertising’s most challenging obstacle is overcoming the public’s conviction that we are less trustworthy than their friends.

Which says as much about our time as it does Hopkins’. For his was a time when radio and railroads and the automobile were tying the nation together in new and exciting ways. No longer was the local choice the only choice. And no longer was the local opinion the only one. Hopkins not only knew this, he used it, championing the citation of literally hundreds of experts whenever possible.

But we are suspicious of these experts now. They have lost their impartiality, or at least we think they may have and we’re too busy to find out for sure. So we rely on our friends, delegating decisions to them because we know that they know that if they steer us wrong we’ll bring it up at every Thanksgiving from now until Armageddon.

And just when you are ready to give up, there’s Hopkins cheering you on from the sidelines:

Advertising often looks very simple. Thousands of men claim ability to do it. And there still is a wide impression that many men can. As a result, much advertising goes by favor. But the men who know realize that the problems are as many and as important as the problems in building a skyscraper. And many of them lie in the foundations. p. 281

And you take another shot at that headline. Just like Hopkins would have.

Scientific Advertising by Claude C. Hopkins was re-published by McGraw Hill on 1/11/66 (with his other groundbreaking book My Life in Advertising which is reviewed here) – order it from Amazon here or from Barnes & Noble here – or pick it up at your local bookseller (find one here).

Please be advised that The Agency Review is an Amazon Associate and as such earns a commission from qualifying purchases

You May Also Want to Read:

by Claude C. Hopkins

by Stephen Fox

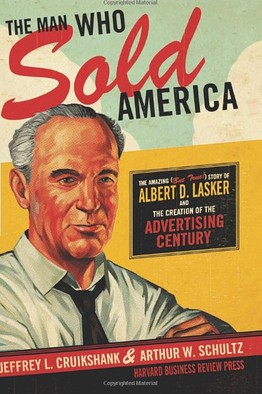

by Jeffrey L. Cruikshank & Arthur W. Schultz

I disagree both with your conclusion and Hopkins. Customers, whether “Sales made by conviction…” or by recommendation, are not loyal. You are right in that times have changed. Consumers are inundated by ads everywhere, cellphone apps, social media, web pages, television, radio and even at the movie theaters! The advice our friend from Hopkins day is now the constant barrage of advertising from our “friends” pushing their products.

The only thing that changes the context & content is time and technology. The needs, like The Song, Remains The Same. Yes, the Human Nature will forever be the same, the media landscape and the speed is all that has changed. Hence, Marketing Science should be place back in it’s rightful place; at the top of the pyramid. The rest is the romance in the execution or the re-contextualization of the same proposition -for the same Human needs- in the now.

As a matter of fact.

Video expands more on topic at hand (and much better than me):