Da Vinci once said that simplicity was the ultimate sophistication and Einstein that “if you can’t explain it to a six-year-old you don’t understand it yourself”. For centuries, geniuses have praised the pursuit of simplicity as the aim of all creation.

So why are things still so damn complicated? And why do we need a book from an advertising agency to remind us of the error of our ways?

Brutal Simplicity of Thought (How it Changed the World) began life as a training manual for Saatchi employees – a book, as the endnote explains, whose “approach shaped the Saatchistory for 40 years. Its principles permeate the culture, philosophy and structure of one of the best known corporate brands.

It is an exceptionally brief – one is tempted to say, simple – missal, tipping the scales at just over a hundred pages, most of which are full of the white space that devotees of Helmut Krone love. Indeed, it is entirely possible that this review will run to more words than the book itself does.

Briefly then, the book has two parts: a long (by the comparative standards of the rest of the book) essay on why, as Mr. Saatchi explains “if you want your work to achieve the impossible, you will need Brutal Simplicity of Thought.” And a series of examples of said simplicity that changed the world, delivered in artful two-page spreads.

(There is also a website (brutalsimplicityofthought.com) which readers are encouraged to visit for the latest examples and to contribute their own to the mix. When we visited, the most recent examples were somewhat less compelling and artfully wrought than the ones in the book, but this is to be expected from crowdsourced content.)

Reading Brutal Simplicity… it occurred to us that there are also two parts to simplicity itself. First, there is the ability to winnow your complicated and chaotic thoughts down to their essence, excising all the extraneous – hell, figuring out what is extraneous and what is essential – until you arrive at a simple, clear, and perhaps revolutionary idea that can withstand the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune.

And the second part is the ability to articulate that idea simply. This is not as obvious as it sounds and neither is it merely a matter of vocabulary. Indeed, perhaps the reason that great art is often difficult to understand is because the very words, images, and structures that we use to convey its message must be reconfigured and rearranged in order to express it. Or perhaps because, frustrated in their efforts to explain their new discovery, and exhausted by the rigors that led to their insight, many creators fall back on jargon, thus describing imprecisely that which they have labored to bring back from the mountaintop.

In its best moments, Mr. Saatchi’s book fulfills the best of both parts of simplicity and elicits refreshing “a-ha” reactions – as when he describes Heinz’s decision in 1869 to become the first company to sell their products in clear packaging. Why? So consumers could see that they contained no fillers and that they were fresh. Because showing is always more powerful than telling. That’s brutally simple. That’s world-changing.

But at other times the language fails the insight and the “world changing-ness” of the thought is not delivered by the brutal simplicity of the communication. Is the brilliance of chopsticks (p. 77) really just that it fed a continent? Is the first photo of earth (p. 90) really the thing that triggered the global dominance of brands? It is at moments like these that one is reminded that brevity is not the same thing as simplicity (as anyone who’s had to correct freshman haiku poetry can tell you) and that an empty page can be just as obtuse as a cluttered one.

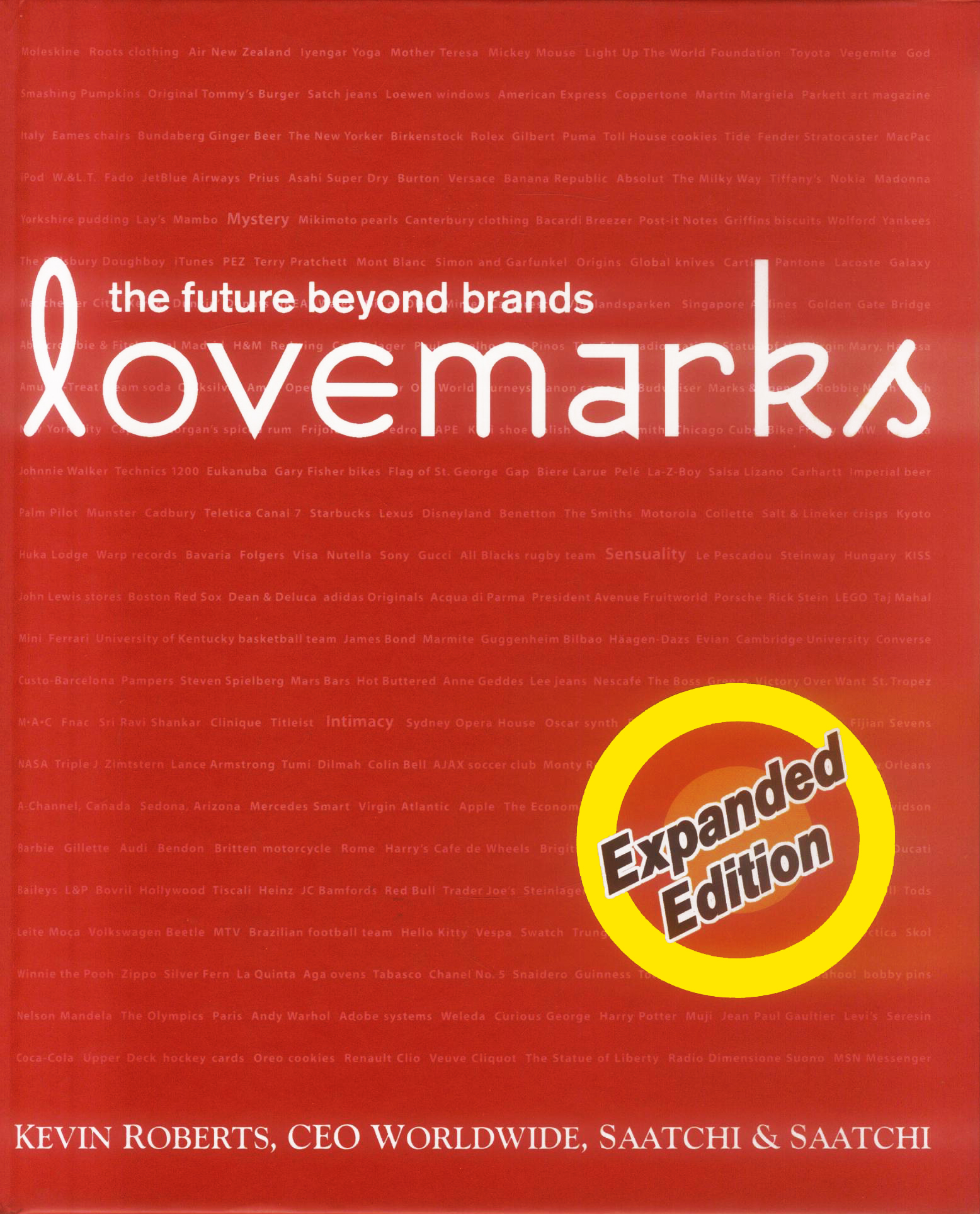

Brutal Simplicity… is also remarkably (one might say “refreshingly”) empty when it comes to portfolio work – because let’s face it, as Humankind was for Leo Burnett, Lovemarks for Saatchi & Saatchi, and even Confessions of an Advertising Man for Ogilvy, this book serves to promote the agency that spawned it. But Saatchi instead prefers to showcase the thinking that clients will buy, instead of the thinking that someone else has already bought. Indeed, the only place we noticed a reference to any Saatchi work was in a list of three famous slogans that won elections for British prime ministers. One, of course, is the “Labour Isn’t Working” tag that gave the world Margaret Thatcher.

Which may be the best example of brutal simplicity in the whole book.

Brutal Simplicity of Thought by M + C Saatchi was published by Ebury Publishing on 11/21/11 – order it from Amazon here or from Barnes & Noble here – or pick it up at your local bookseller (find one here).

Please be advised that The Agency Review is an Amazon Associate and as such earns a commission from qualifying purchases

You May Also Want to Read:

by Tom Barnardin &

Mark Tutssel

by Kevin Roberts

Kevin Roberts, author of Lovemarks

One thought on “Brutal Simplicity of Thought”