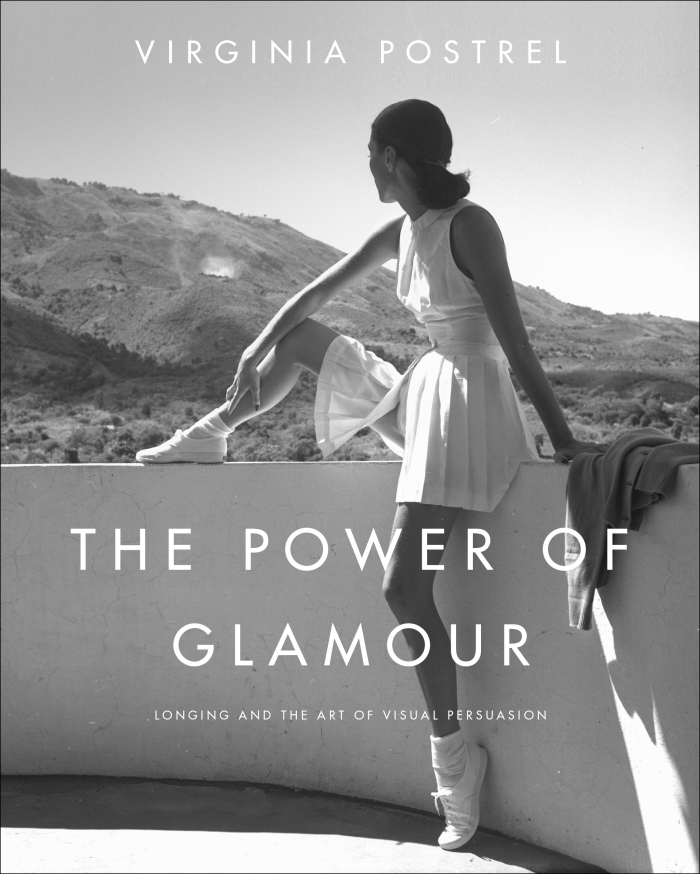

Author, TedX speaker, and columnist Virginia Postrel started out as a reporter for Inc. Magazine and then the Wall Street Journal, before becoming editor at Reason magazine. She has written for the New York Times and the Atlantic magazine, and currently writes a bi-weekly column for Bloomberg View. The author of several books, including The Future and Its Enemies: The Growing Conflict Over Creativity, Enterprise, and Progress in 1998, and The Substance of Style: How the Rise of Aesthetic Value Is Remaking Commerce, Culture, and Consciousness in 2003, she most recently published The Power of Glamour: Longing and the Art of Visual Persuasion in 2013 (which we reviewed here). Ms. Postrel, whom you can reach here, recently took some time away from her research for a future book on textiles and technology, to speak with us about glamour and its discontents.

genesis

Agency Review:

We admit that we were surprised by The Power of Glamour – how it took a topic that we ignorantly dismissed as a superficiality and unfolded it to reveal its depth, value and relevance. Was this the way you had always perceived glamour or was there an event that brought you to a new realization about it, that set you on the path that ended in the book?

Postrel:

I hadn’t thought much about glamour until 2004, when a curator at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art asked me if I’d write the introductory essay to their catalog for an exhibit on glamour in architecture, fashion, and industrial design. I’m not sure what he meant by “glamour,” but the exercise made me think about it and resulted in my first cut at the subject. (I did a TED talk based on that essay, long before I decided to write a book.) I’ve always been interested in the “unglamorous” side of things—the hidden details, such as logistics in business—so it was an unlikely subject for me.

Agency Review:

But wait, if your background was more on the logistics side and business side, why do you think Joseph Rosa chose you to write the introductory essay? Doesn’t that seem a bit of a stretch?

Postrel:

Joe had read The Substance of Style, which is about why aesthetics—the look and feel of things, not the philosophy of art—has economic value. This was in those long-ago days when it was a new idea that your computer or cell phone might be something other than a clunky functional machine or that a business hotel room might be attractively designed.

It’s not that my background was more on the logistics side but that my interests tend to lie in what’s hidden or underappreciated. Glamour tends to disguise those things. But it turns out that glamour is, in fact, underappreciated. And once I got interested in the puzzle of what exactly glamour is and how it affects many aspects of life I kept thinking about it.

beauty

Agency Review:

We would be remiss if we didn’t compliment you, Nancy Singer and Simon & Schuster on the look of the book. It is exceptionally beautiful – from the terrific art and illustrations to the elegant design to the graceful lay out; I would even guess that the printing itself required a bit of an extra mile from the production department. So, how important to you was it that a book about glamour was itself glamourous-looking?

Postrel:

It was tremendously important to me. I see the illustrations as a kind of visual soundtrack accompanying the argument. That’s why some just appear without captions. They’re supposed to help you feel a certain way and to illustrate that many different kinds of images can create those images.

Agency Review:

“Visual soundtrack” is an interesting way to talk about it. Did you consider creating an actual soundtrack on social media, say, Spotify for example? Or do you think glamour doesn’t translate to the auditory as well as it does the visual?

Postrel:

I’ve tended to ignore the potential for auditory glamour, perhaps because I simply don’t have the expertise or vocabulary to understand it. But when I was writing and editing the group blog DeepGlamour.net, one of our chief contributors was a composer named Randall Shinn, who has thought about glamour and music.

Agency Review

To go back to our discussion of the visuals -the design of the book feels like an interesting interpretation of McLuhan’s famous “medium is the message” idea – that you wanted to create a document that was as much an example of what you were talking about as what you were talking about was. Yes?

Postrel:

Exactly. At times that made finding appropriate illustrations difficult, because the book’s audience wouldn’t react to, say, a Ukioye print of a popular beauty or actor the way a Japanese audience in Edo at the time would have.

organization

Agency Review:

One of the impressive things about your insight into glamour is how you find it touching so many things. From its history to its expressions to its impact. And we’re assuming that the discovery of this breadth wasn’t a linear experience – and even if it was, selling a chronological history of glamour was probably an impossible task. So how did you develop a plan for organizing all this different information and insight into the cohesive, and compelling narrative that we reviewed?

Postrel:

The structure of the book wasn’t a huge challenge. I knew I wanted to build a theory first and then apply it through history. Even though many readers find the historical chapters the most compelling, to understand them you need to have had the exploration of what glamour is and how it works first.

Agency Review:

Exactly – the exploration provides the context for the history. Otherwise the history simply becomes an unilluminated litany of beauty and style.

Postrel:

The hard part was the research. When I wrote the original essay I started by reading up on the obvious targets—Studio-era Hollywood glamour, fashion, and travel—and trying to figure out what they had in common. I also thought about the meaning of “glamorous” and “unglamorous.” Beyond that, glamour is a difficult topic to research. There’s no “glamour” section of the library, the way you might research design or architecture or even, to go back to chapters in my first book, knowledge or play.

Agency Review:

If there were a glamour section of the library, though, it would be fabulous…

Postrel:

And I didn’t find interviews terribly helpful either. I wound up relying heavily on serendipity and conversations with friends, many of whom would send me examples they found. The wonderful story about Michaela DePrince that opens the book is something my husband heard on the radio. He told me about her and I then did further research.

Agency Review:

This just makes your accomplishment all the more impressive. Though it does make us wonder if there may be other areas of expertise or insight that are similarly overlooked. Our friend and African-American historian, the late Jim Miller, used to talk about “the archive” of African-American history not being in books and museums, but being spread out across the nation in countless homes and attics and basements and family photo albums and even just in the memories of people. A living, breathing thing, but that much harder to track down. So too with glamour?

Postrel:

It’s in people’s heads. For example, a woman recently told me about how reading the book reminded her of how seeing a commercial of dancing women dressed as cigarette packs (she called them “cigarette girls” but that made me picture something entirely different) was incredibly glamorous to her as a nine-year-old watching TV for the first time in 1952. She wrote to me afterwards that

“what was glamorous about those women is that they showed women in roles other than those of housewife, teacher, nurse, and secretary. What an idea! The world was a wider place than I had imagined! For me at the time, the elements glamour — transformation, grace, and mystery — were all in that performance.”

reaction & categorization

Agency Review:

It has been our experience that when something as fundamentally insightful as your analysis of glamour is presented, there is usually a lot of negative feedback, if for no other reason than because the new thinking fundamentally challenges the perceptions that many have constructed their realities upon. So how was the book received and were you surprised by the reception? It can’t have helped that the book, while nominally categorized as “Social Science” doesn’t fit easily into any one bookseller category.

Postrel:

The category problem hurt the book’s sales tremendously. It’s accurately classified as “cultural studies,” but it turns out that when you go into a bookstore most of the books in that category are about food. The bigger problem is that most people seem to think that “glamour” equals “fashion” and most fashion people aren’t interested in intellectual books and don’t know what to make of it. It got a positive review in the New York Times Book Review but the reviewer, who actually has a Ph.D. in comparative literature, found it too intellectual to be glamorous. “There is little here to set the readers of InStyle magazine dreaming,” she wrote, as if glamour were limited to fashion.

Agency Review:

Actually we don’t think that’s far off the mark (though as you say, the rest of the review was pretty positive) – for it speaks to the flip side of our previous question. Does a glamourous-looking book runs the same risk that glamour itself has run – to be dismissed as superficial and fashionable, until one digs deeper and discovers what it reveals about ourselves? So was there any consideration of that during the design process? That the book should, perhaps look more “academic” and less “beautiful” in order to be taken seriously?” Or perhaps for the paperback?

Postrel:

There was more discussion about the title, since so many people associate glamour with fashion or exclusively with women. Early on there was some discussion about whether “glamour” should be in the title or the subtitle and, if so, how. My preferred title was Decoding Glamour or Glamour Decoded, which has a more intellectual edge to it and describes what the book is doing. (“The Power of Glamour” is also the title of a different book, published in 1998, about glamorous women.)

a golden age

Agency Review:

At one point, as you address why the 1930s appears to be the era of glamour, you write:

“We remember this period as glamour’s golden age, then, because it expanded the audience for glamour, established a common international culture of glamour and intensified the identification between audiences and glamourous icons.”

Curiously, we are currently living through an age which, because of the internet, is experiencing an expanded audience and a growing common international culture which intensifies a connection, if not an identification between audiences and icons. Which raises the question: are we entering a new golden age of glamour?

Postrel:

Today’s audience is expanded but it’s also highly fragmented, so rather than a common international culture of glamour we have many, many subcultures. They’re just divided more by personality and identity than by geography. In fact, one of the big challenges of writing a book on glamour now is figuring out what is glamorous to people who are quite different from you. Why do young men go to fight for Islamic State? Why is there a fad for “tiny houses”? Glamour is a big reason.

Agency Review:

But does that lead us to consider that perhaps an “international culture of glamour” was something of an anomaly – unique to a specific time. That while glamour is and does what you say, it’s possible that the “unfragmented” aspect of it may have been a phase. For what was glamourous in Japan in the Edo was not what it was in, say, Melville’s America. What was glamourous in the House of the Medici wasn’t at the foot of the Dragon Throne?

Postrel:

I would agree with that in general, although I did discover to my surprise that there were amazing parallels between forms of glamour in commercial cities. In Edo and Paris, which had no contact, you see the theater and demimonde, becoming sites of glamour, even to the point of people buying posters of their favorite actors, although the styles are different. Commerce and theater produce glamour.

Agency Review:

That is surprising… and not a little fascinating…

Postrel:

I agree. But circling back to my point about how glamour is different for different people – I recently wrote an article in the Washington Post about Donald Trump’s glamour. To me, he’s the antithesis of glamour—charismatic, yes, but graceless and not representative of any transformation I’d desire. But I interviewed Trump supporters, including an insightful entrepreneur who’d read and understood my book, and I came to realize that for a certain segment of his supporters he is in fact glamorous. It’s not because he puts a lot of gold on his furniture, but because he seems to represent effortless business success.

Agency Review:

Which would seem to reinforce what we were talking about – which is comforting because it’s something we’ve been wrestling with for a while. There seems to be a perception that American culture was somehow not fragmented in the past – a belief anchored by things like there being only three television networks, so everyone saw the Beatles at the same time, etc. etc. But American culture has always been fragmented if you got out of your own tribe long enough to see it. That’s why black folks didn’t need English kids to introduce them to the blues – even though white kids did.

Postrel:

Absolutely true. Having grown up in the South in the 1960s and 70s, I’m acutely aware of how the mid-20th-century idea of “American culture” was a media artifact that left certain things out, including big, important things like evangelical Protestantism.

the future of glamour

Agency Review:

And now, let’s take the other side of that last question. You write mid-way through the book “There is no glamour without mystery” and we believe you’re right. But the flip-side of the connectedness, expanding audience, and access that the internet and social media provide is a heretofore never experienced level of over-saturation, where privacy, let alone mystery, is increasingly difficult to come by. Thus do you believe, as Brian McCollum seems to, that glamour may no longer be possible?

Postrel:

When the book was new, audiences often asked this question, usually with some kind of reference to Kim Kardashian. I’d point out that we only know about the celebrities who choose that strategy. There are plenty of public figures who still have an aura of mystery about them, because they only share so much with the public.

Agency Review:

Wait “we only know about the celebrities who choose that strategy”. Can you give us some examples of celebrities – current ones (not Garbo, for instance) who have chosen a different strategy, and even what that strategy might be?

Postrel:

Cate Blanchett is an example I use in the book. She does it through ambiguity, the kind of mystery I call “sparkle.” She’s a chameleon as an actress, so you can’t equate her with her roles, and she presents contradictory sides of her personality to interviewers. Kate Moss is another example in the book. She’s everywhere but keeps her mouth shut. Denzel Washington, who is frequently voted America’s favorite movie star and is almost always in the top three, is generally private. In fact, most celebrities don’t display much about their personal lives in public.

Agency Review:

So ambiguity, reticence, privacy…

Postrel:

But what was really interesting was how the question changed over time. People no longer ask about mystery and celebrities. They ask whether ordinary people are all creating glamorous images of our lives through social media. And I think that’s right. Yes, a few people use Facebook to gripe about what ails them, but not many post ugly pictures on Instagram (which has made retouching an everyday experience) or tell you about the boring details of their lives. We’re creating selective, glamorous visions of ourselves.

Agency Review:

That’s an exceptionally fascinating point, because it speaks to an argument we’ve had with advertising people specifically about social media. Their contention was that it was a great opportunity for the clients to see how their customers really lived, while ours was that what you saw on social media was, in a sense, the best version of people. Only the best pictures on Instagram. Only the wittiest comments on Twitter. Hell, even the trolls were being far troll-ier on line than they’d be if you actually met them in real life.

Postrel:

I wonder whether when we look back in five or ten years, having forgotten much of our everyday experiences, we’ll think, Wow, everything was so much better back then!

Agency Review:

But the problem is, none of this is transformative, to your point earlier about Donald Trump. It may be aspirational but to whom, beyond the person making the glamour themselves? Further, one of the insights you had about glamour that we thought was particularly resonant was that it struck this remarkable balance between acknowledging what was and what was aspired to. The viewer knew what was in their own life, when she looked at, say Jackie Kennedy, but she also knew what she aspired to. That dynamic doesn’t seem to come into play in the social media world of ordinary people, does it?

Postrel:

That balance was the subject of one of the most astute early reviews of the book, by Autumn Whitefield-Madrano, who writes on beauty (and now has a great book out herself). She was struck by my seemingly bizarre example of Star Trek, because it rang true to what she saw in her brother:

“My brother couldn’t wholly identify with life aboard the starship Enterprise, but he saw enough of its world in himself—and he saw enough of himself in the values of that world—that it became far more than mere entertainment to him, even if he couldn’t spell out why. Star Trek wasn’t remotely glamorous to me, but it was to him.”

That then led her to consider how glamorous beauty images work for women.

Agency Review:

Fascinating…

Postrel:

Now, when we say “social media,” it depends on which platform we’re talking about…

Agency Review:

Of course…

Postrel:

Pinterest users are quite clear about using it to express aspirations and sometimes those aspirations are explicitly designed to become realized, in interior design or wedding planning, for instance. (Of course, what the external style represents internally is a different question.) And there’s interaction among different people’s boards, as pins and the aspirations they represent get shared. I suspect that Instagram and Facebook photos do transform people in subtle ways—you seek out experiences that lead to appropriate photos—and then people who follow you emulate that. Look at how Kim Kardashian has promoted waist-training. But it’s a good question. No one really understands where the exponential proliferation of images will lead.

You can read our review of Virginia’s book here, or order it from Amazon here or from Barnes and Noble here – or pick it up at your local bookseller (find one here).

Illustration of Virginia Postrel by the brilliant Mike Caplanis

Please be advised that The Agency Review is an Amazon Associate and as such earns a commission from qualifying purchases

You May Also Want to Read: