Fritz Grobe and Stephen Voltz are the masterminds behind the “Diet Coke and Mentos Experiments” which went crazy viral (17 million views and counting) enabling them to launch EepyBird, where they “spend countless hours searching for ways to transform these things from everyday life into something new, into something unforgettable.” Their book The Viral Video Manifesto (which we review here) not only identifies some terrific rules and guidelines for helping things go viral, it also provides dozens and dozens of examples which are as entertaining as they are instructive.

Grobe, who ran away from a mathematics degree at Yale to join the circus (more or less) and Voltz, a practicing lawyer, part time juggler and former street performer, agreed to sit down with us to discuss virality, advertising, clients and where they all overlap.

risk

Agency Review:

One of the most valuable insights about viral videos that you make is, frankly, one that I was not expecting. Namely, that most companies are culturally incapable of being as risky as success demands. In fact, we quote you extensively on the subject during the review. As someone who’s been asked to make viral videos for clients, we couldn’t agree more. But when did you realize this, and how, and what is it like to explain to clients that they just aren’t capable of success?

Stephen Voltz:

This was something it took us a while to figure out. It was only when we looked back at conversations we’d had with some brands that hadn’t gone in the directions we thought they should have that we realized there was a pattern. Having said that, however, I don’t think I’d say that brands aren’t capable of being different enough to stand out and go viral. I think they can be. What we try to help them realize is that there’s a bigger and more predictable risk in doing what everyone else is doing – which is that no one will watch your work and all the time and money you spent creating it will go down the drain without a sound.

Agency Review:

To be clear, I wasn’t saying that brands aren’t capable across the board; I was focusing on the idea that companies are, by and large, set up to avoid doing things that are risky. And, as you point out, risk is central to viral.

Fritz Grobe:

Absolutely. We have had many clients who gravitated to ideas that didn’t stand out from the crowd, and those ideas just won’t go viral. There’s a very natural tendency to do exactly what everyone else is doing, but to go viral, you’ve got to stand out from the crowd in some clear way. You need to create a sense of, “I’ve never seen that before!”

Agency Review:

How much of that is ignorance of the medium (e.g., they don’t know that their idea’s been done to death) and how much is fear of risk?

Fritz Grobe:

I think it’s a bit of both. We push clients to take their ideas far enough to become unforgettable. It’s easy to confuse risk-taking with being wild and crazy, which may simply be off-brand. But brands like Sony Bravia, TNT, and Volvo have made wildly different, beautiful, on-brand videos that took artistic risks: being bold and daring enough to capture people’s imaginations.

Agency Review:

So do you seek out clients who appear to be aware of the value of risk, who have some how demonstrated an understanding of it – and if so, how do you identify those clients? Or, do you lay out ground rules at the beginning – much like you do in the book – and say “if you’re not willing to do these things, you’re just wasting your money with us”? And if it’s the latter, how do you hold them to that without feeling like the scolding schoolmarm?

Stephen Voltz:

We find it a lot easier to work with brands that are already at least somewhat on the same page with us. It helps to see what they’ve done before, but we learn a lot in the first conversations we have with them.

Fritz Grobe:

Like any business, we’re trying to provide the best possible value to our clients, and for companies that really want to make a TV commercial, not a viral video, we’re simply not a good fit. The strength of online video is creating an emotional connection. That connection is what gets videos to go viral. We emphasize with new clients that that’s where we can provide value.

guidelines

Agency Review:

You have some very specific do’s and don’ts that, in your estimable opinion, will increase the likelihood of a viral video’s success. We don’t disagree with them, but most guidelines didn’t develop in a vacuum. They were the product of trials and errors, disastrous missteps and subtle tweaks that had huge consequences. So how did you come upon these guidelines – and don’t tell us it was simply a case of reverse engineering the success of Diet Coke/Mentos.

Stephen Voltz:

No, indeed, it wasn’t simply a matter of reverse engineering what we had done with Coke and Mentos; it was the result of analyzing literally hundreds of videos that had had viral success as well as videos that had tried to go viral and failed.

Agency Review:

That’s great to hear, because a lot of the books we read feel like the authors had a hit, then wrote a book saying “the only way to have a hit is the way we did it,” creating this weird, self-fulfilling feedback loop that is devoid of real insight. It didn’t feel like The Viral Video Manifesto did that, and we’re glad to hear it wasn’t the case.

Stephen Voltz:

In The Viral Video Manifesto, we discuss over 150 different viral (and a few non-viral) videos, and we looked at many times that number of videos in researching the book. It was from looking at all of them that we were able to tease out, more globally, what works and what doesn’t and it was that process that lead us to develop our Four Rules.

Fritz Grobe:

We also had a particular learning experience ourselves with The Extreme Sticky Note Experiments where the video got away from the original concept of amazing images created with thousands of sticky notes and turned into more of a story: there’s an office where the boss is a bit of a jerk and we’re the two mischievous workers… The video did well and won some nice awards, but afterwards, we realized it could have been better constructed for viral spread. That experience led us to understand that, for viral video, story is an obstacle. When you’ve promised amazing sticky note experiments, get to it right away. Those kinds of experiences really shaped our Four Rules.

Agency Review:

Funny you should mention awards – because that brings up an interesting challenge that new forms face: they are constantly judged against criteria that are more or less irrelevant for them and it takes time for people to discover what the appropriate criteria are. That’s one of the things that makes The Viral Video Manifesto great – it’s hit on the appropriate criteria. So are you finding people embracing your Four Rules?

Stephen Voltz:

Yes, they do seem to resonate. And as brands have more and more experience in the medium, what they’re learning often coincides with what we’ve been advocating.

Fritz Grobe:

Particularly when we started explaining that viral video isn’t about conventional storytelling, that was tough for a lot of clients to understand. But now, it’s easier to explain and easier to see that viral video is, as we say, the 21st Century sideshow – promise me something new and amazing, then deliver. Whether it’s Felix Baumgartner jumping from the edge of space or Jean-Claude Van Damme doing the splits between two Volvo trucks, you can really see our Four Rules in action.

craft and reality

Agency Review:

There’s a deeper observation at the heart of your book that we found really fascinating – that one of the things that has made advertising less effective is the very professionalism of its craft. That is, its very slickness. And correspondingly, a lot of the tips and advice you give are basically ways to make the videos feel “realer” by foregoing that look of professionalism. Why? What do you think it is about the way advertising is done that makes it less engaging than it once was?

Stephen Voltz:

For most of the history of modern advertising the big players were radio and television where the goal of the networks was to keep listeners and viewers tuned in at night until they were so exhausted they fell asleep. That led producers to develop content – both programming and advertising – in a style that encourages passive, continuous viewing. The production techniques that we think of as making content look more “professional” – quick cuts, odd camera angles, sound effects, news crawls, and the like – are techniques to keep viewers watching and listening, in an almost hypnotic state, regardless of what the actual content is.

Online, things are very different. Passive viewers don’t help content spread across the web. For content to spread virally, you need to get viewers to be ACTIVE, to stop what they’re doing and tell their friends about what they’ve just seen.

And that requires a whole new set of tools.

One of the most important principles we discovered is that content that goes viral is content that’s authentic. That’s our very first principle – Rule One: Be True. People tell their friends about things that are real. And every traditional production technique you use tells people, subconsciously, that what they’re seeing isn’t real, it’s manufactured. Ultimately, that’s why the techniques we’ve all learned from film and television actually hurt you when you’re trying to create something viral.

Agency Review:

That idea that online requires different tools because it’s a fundamentally different user experience – and because fundamentally different things are expected of the user – is huge, and doesn’t just apply to Viral. Every media is a different user experience, and the truly successful executions are the ones that recognize that.

That said, I fear you’re in some difficult territory when you talk about being “true”. You guys were in white lab coats in the Mentos vids, but you’re not scientists. Did it add to the drama and comedy of the piece? Of course. But was it strictly “true”? Was it even “true” in the way that the guy with the bricks on his head was “true” – capturing an event that was not constructed for the reason of being video’d.

Now, I’m not beating up on you guys, honest. I think you’re spot on in a whole bunch of areas. I just wrestle with “true” because I think it’s a highly volatile idea in the least of times, but especially when we talk in terms of marketing.

Stephen Voltz:

Actually you raise a really important point. For the kind of viral videos we make, you can and should prepare, and even rehearse, your piece before you record it and put it online. You want to nail it in one take, and to do that you need to practice it. But, as Fritz mentioned earlier, we also believe that viral video is the 21st Century sideshow. Some of the sideshow acts know that that’s what they are, and they do what they do on purpose. That group includes folks like us, OKGo, Felix Baumgartner, and the like. Others, like the FAILBlog videos, wind up as sideshow acts by accident.

With us, our piece involved wearing lab coats and setting up a 100+ bottles of Diet Coke out in the woods. We didn’t expect people to really think we were scientists, we just wanted to present a fun, off-beat sideshow act. Then, within that framework, we tried very hard to be true. We worked to make clear exactly what we were doing and to offer it up as an honest and straightforward (if silly) presentation of what happens when you drop Mentos into that many bottles of Diet Coke and choreograph it all to music.

Fritz Grobe:

For us, the major warning bell on Rule One: Be True is if there’s supposed to be “Acting” involved. Are there characters and a plot and a script? That’s dangerous for viral video. The more you simply capture something real and the more you share who you really are, the better. We aren’t scientists, but we are geeky guys who are genuinely excited to pull of these crazy stunts – from the Coke Zero & Mentos rocket car to turning a quarter of a million sticky notes into paper waterfalls. We work to keep the focus on the truth, the reality of those stunts, and create an emotional connection through our genuine sense of accomplishment in achieving these absurd extremes. No acting necessary.

money shots

Agency Review:

You dedicate an entire chapter to “Money Shots” which we’d like to explore a bit more. It seems that you’re saying “you don’t need as much set up in viral videos as you do in other forms – what you need is a killer money shot, a killer punch line.” And we get that. But, “set up” is another word for “story” in most cases, something that contextualizes the punch line or money shot. And so we’re wondering if the way you get around that is because in viral videos, the story is often culturally contextual, so you don’t need a set up (that said, admittedly some things are just contextual to life – e.g., the “Dude transports 22 bricks on his head”). And further, do you think this is something that’s limited only to online video, or do you think it’s applicable more broadly to culture?

Fritz Grobe:

Our focus on money shots comes from our work in circus and sideshow, where if you have a sword-swallower, we don’t want to hear her life story – we want to see sword swallowing. Television has trained everyone into providing lots of background information: every time the Olympics roll around, we’re about to see the best gymnasts in the world, but first, let’s look at where they came from… For viral video, this kind of context just slows things down. If you’ve promised us “Dude transports 22 bricks on his head,” do you think we then want to see him getting ready for work or talking to his kids? For a documentary, yes. For viral, just show us an insanely big stack of bricks on his head. Make a promise and deliver as efficiently as possible.

Agency Review:

It occurs to me that in that example, the set up is in the title – “Really? 22 bricks? I gotta see that!” You already know why you want to watch. With the Olympics, not so much “Here’s the third Lithuanian diver. Ready?” “Well, no.” “How about if I tell you she’s blind and an orphan and can’t swim?” “Now you’ve got my attention… You should have called her ‘blind orphaned non-swimming diver competes in the Olympics!’”

Fritz Grobe:

Absolutely. A video of “the third Lithuanian diver” – unless, as you say, there’s a big surprise involved – is unlikely go viral. On TV, they’re stuck with the problem of trying to make the third Lithuanian diver compelling through story. For viral, you don’t want content that you have to try to dress up to keep people watching. For viral, you want content that is, all by itself, compelling. Video of yet another Olympic diver doing yet another solid dive – probably not viral, no matter how you dress it up. Video of a regular guy trying to jump into a pool that is frozen solid – there’s a hook, and that video went viral. There’s a video that needs only a simple setup before a great payoff.

Stephen Voltz:

You do need setup and context. Without it whatever your punchline is will be meaningless. This is true of even the simplest, shortest viral video. Sneezing Baby Panda is only 16 seconds, but 11 of that is setup. Our experience is that your video will be more viral if you make the setup as ruthlessly brief as possible. For the classic JK Wedding Entrance Dance, the first few seconds of the church with guests seated and ready for a wedding to being is all they needed.

And now that you ask, that probably is true more broadly, too. The urge to pad things around the “money shot” and make everything longer than it needs to be probably starts in school when we’re told to do things like “write a 10-page paper” (as opposed to a paper that clearly explains something) and continues up through to anyone whose job it is to crank out content of any kind on a regular basis. If you have to come up with 22 minutes of “news,” or 7 column inches of opinion, or “2 articles on healthy eating,” every day, tricks to pad your core content (your money shot) quickly become your friend. They’re the enemy of good writing however, even as they help you pay the bills day to day.

My personal guideline, and this applies to whether I’m making a video, giving a speech, writing a book, or back when I was practicing law, trying cases, comes from guitar legend Carlos Santana. When asked about how to approach playing a solo, he answered simply “You get in, do what you gotta do – and get out, man!”

Those are words to live by.

Agency Review:

I’d be a fool to argue with Santana, so I’m not gonna try. Not only because he’s a Hall of Fame Rock and Roller, but because I completely agree with him. And with you about people focusing erroneously on length (which, let’s face it, is arbitrary) instead of content. My father used to quote Einstein about it: “Make everything as simple as possible, but no simpler”. Form following content following form.

But I’m sure you find yourself dragged into meetings with people who start second guessing and overthinking. I would imagine that’s what happened in The Extreme Sticky Note Experiment – “People won’t know why this is happening in an office, so we better explain that. And they won’t understand who these people are, so we better explain that.” And what you cut ends up being very personal – “I understand this is implied, so we don’t need it” “Well I don’t, so I think we do.” So how do you navigate that?

Fritz Grobe:

It’s always easy to overthink, and it’s a constant battle to keep everything as simple as possible.

Stephen Voltz:

We try to get everyone on board with the idea that story only hurts us and that the only shots we can afford are shots that bring the viewer information he or she needs to understand to appreciate whatever comes next. If everyone agrees that that’s the rule, we’re usually alright.

future

Agency Review:

Viral videos are a media just as legitimate and valuable as any other and one of the great services your book provides is it lays out the ground rules for that media, as have been laid out for other media over years and decades. And that’s always the first hurdle, right? What is this and how does it work? But this phase is usually followed by people taking those tools and creating stuff we never could have imagined when we were in the initial “Whoa, what is this?” phase. So, what do you think is next for viral videos? More? Different? Yes? How?

Stephen Voltz:

I’m not sure where viral video is headed, but one trend I’m noticing is that, with branded content, it’s getting tougher and tougher to tell what’s viral and what’s got a lot of views simply because of heavy promotion.

Don’t get me wrong, putting budget into promotion is important, but figuring out what’s going viral and why has gotten harder because view counts alone don’t any longer determine if something is viral.

Agency Review:

Interesting. In other words, the efforts of Twitter and Facebook to monetize by allowing advertisers to “buy” success on their sites (which they would argue is just like letting an advertiser dial up their media buy on a tv show) actually muddies the measurement, generating, at best, less faith in the media itself.

Stephen Voltz:

Yes. Not to say there’s anything inherently wrong with buying viewers. That’s what TV is all about and it works wonderfully. It does mean though that judging what’s “gone viral” takes metrics other than simple view counts.

That said, the Four Rules of Viral will likely remain true for a long time because – and this wasn’t something we realized until after we’d written the book – they’re really just the basic rules for good human communication: Be True, Don’t Waste My Time, Have Something to Say – Be Unforgettable, and Ultimately, it’s All About Humanity.

Fritz Grobe:

Things that were once strange and unforgettable can become normal, so what stands out from the crowd will evolve. But whether it’s on YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, Vine, or whatever comes next, as Stephen says, the Four Rules in our book are fundamentally about human communication: be honest, get down to business right away, show us something we’ve never seen before, and show us who you really are. While the medium may change, the ways to communicate and the methods for getting people to share positive emotion with their friends will remain much the same.

Agency Review:

You’re right, of course, and we’ve argued that those rules, or rules very much like them, are the real measure of any marketing campaign. What makes “Think Small” so brilliant, what makes “1984” so great, what makes even “the Marlboro Man” so resonant, are their adherence to those ideals. And yet, marketers don’t seem to understand that (because one would think that if they did, they’d buy better work). Why?

Fritz Grobe:

I think marketers often get stuck focusing on communicating the features and benefits of their products. And explaining features and benefits can be important. Coca-Cola definitely gets us associating their products with cold, fizzy refreshment. But if, as a marketer, that’s all you’re thinking about, you can miss the bigger picture: creating an emotional connection with consumers. So Coca-Cola is ultimately focused on happiness, and their best viral campaigns like The Happiness Machine show the smiles their products can generate, with great success. Features and benefits are secondary to the emotional connection.

And that emotional connection moves product. Our Coke & Mentos videos saw sales of Diet Coke spike and sustained increases for Mentos, not because we were showing features and benefits. Yes, the videos reinforce the ideas that Coke is fizzy and that Mentos are strong, but most of all, those videos get people smiling when they think of those brands.

Red Bull is edgy and exciting, so that made Felix Baumgartner a good fit for them. When he jumped from space, did you learn about Red Bull’s flavor or other features? No. But they created an emotional connection with millions of people. That’s a big win.

So if marketers are solely focused on explaining that this new computer has a faster graphics card, they won’t create “Think Different.” Again, the strength of viral video is in creating an active, positive emotional connection. It can be difficult, but the potential rewards of that viral connection are huge.

You can read our review of Fritz & Stephen’s book here, or order it from Amazon here or from Barnes & Noble here – or pick it up at your local bookseller (find one here). Or you can reach out directly to them here.

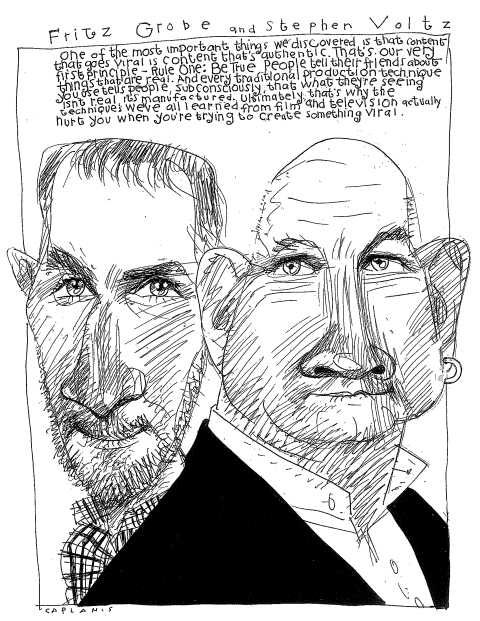

Illustration of Fritz Grobe and Stephen Voltz by the brilliant Mike Caplanis

Please be advised that The Agency Review is an Amazon Associate and as such earns a commission from qualifying purchases

You May Also Want to Read:

by Stephen Voltz and Fritz Grobe